A History of Us – A History of Consumers

Consumer behavior has undergone a significant evolution over the last 600 years, transforming from a concept often linked to waste to a central aspect of modern economies and personal identity.

Here is a timeline outlining these changes:

- Before the 17th Century:

- The term “consumption” generally meant waste or destruction, similar to the disease tuberculosis being called “consumption”.

- In Europe, the High Middle Ages and the Reformation were not primarily characterized by consumption.

- In late Ming China (1520s–1644), novelty was regarded with suspicion. Taste was a mechanism to differentiate against “uppity consumers” and their undesired items. Status was determined by refined consumption, focusing on the harmony of objects rather than sheer quantity.

- Late 17th Century – Early 18th Century:

- Economic commentators began to argue that purchasing goods and services enriched a nation by expanding markets for producers and investors.

- In 1776, Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations famously stated that “consumption is the sole end and purpose of all production”.

- A new consumption regime emerged in northwest Europe, marked by increased volume, variety, and innovation.

- Contrary to popular belief, mass consumption preceded factory-style mass production. Demand from the West for goods like Indian cotton and Chinese porcelain spurred European industrial innovation.

- New goods such as clothes, domestic comforts, exotic tea, coffee, and porcelain became more accessible.

- Mechanisms like second-hand clothes markets, pawnshops, auctions, and gift-giving helped distribute goods more widely.

- By the 18th century, poverty no longer completely barred access to goods; for example, half of paupers in Essex owned tea-related items.

- Mid-19th Century (1860s-1870s):

- Economists like W.S. Jevons, Carl Menger, and Léon Walras developed the concept of “marginal utility,” arguing that value was created by consuming, not labor, placing the individual consumer at the center of economic thought.

- Late 19th Century – Early 20th Century (Around 1900):

- “The consumer” entered the political arena, wielding purchasing power to advocate for social reform in the US and Britain, and later in France and other European countries.

- Department stores and shopping for pleasure became prominent.

- Consumers organized collectively, using boycotts against exploitative practices (e.g., sweatshops).

- The idea that consumers were essential for societal wealth and welfare gained traction, leading to demands for consumer rights and state protection.

- In Britain, the “apotheosis of the consumer” intertwined consuming more with the national interest.

- The period also saw a “renaissance of the material self” (1890s-1920s), fostering a more intimate relationship with possessions and seeing artefacts as embodying individual character and culture.

- First World War:

- The war reinforced a “consumer identity,” particularly in Central Europe, leading to the formation of national committees for consumer interests representing millions of households.

- Inflation broadened the definition of “consumer” to include workers, shifting the perception of the “producer interest” as an adversary.

- Interwar Period (1920s-1930s):

- Youth culture gained prominence, influencing consumer patterns related to cinema and fashion.

- The popular Week-end Book (first published 1924, 1931 edition) advised on “speed-basis” menus for leisurely activities, indicating a move towards convenience in the home.

- Despite the availability of electrical appliances, their diffusion was slow in many rural areas (e.g., only a few households in Douelle, France, had fridges by the end of WWII).

- By the late 1920s, a significant portion of consumer durables, including 60% of furniture and 75% of cars in the US, were purchased on installment credit.

- In Soviet cinema, films shifted from serious political messages to glamour and entertainment by the mid-1930s.

- During the Great Depression, the economic diagnosis shifted from over-production to under-consumption, making the consumer a key player in democratic state-building initiatives like Roosevelt’s New Deal.

- The notion that prosperity depended on consumers’ spending, regardless of work performed, became widely accepted, leading businesses like AT&T to link consumption with citizenship.

- Nazi Germany utilized consumption for political ends, promoting mass tourism through “Kraft Durch Freude” (Strength Through Joy) as an ideal of “the good life”.

- Post-World War II (1945 – 1980s):

- Europe and the US saw a rapid adoption of home appliances, with almost every household in places like Douelle, France, owning a fridge, cooker, and washing machine by 1975.

- In West Germany (1950s), “consuming more” was central to public policy and seen as crucial for economic recovery.

- Desired consumer goods, like the stylish Vespa and Lambretta scooters, became symbols of reconstruction amidst the rubble of post-war Germany.

- The Cold War transformed consumption into an ideological battleground, exemplified by the “kitchen debate” at the 1959 Moscow exhibition featuring US and Soviet appliances.

- Youth culture’s influence expanded, with consumer choices in music (e.g., Elvis records) and fashion becoming central to identity.

- In East Germany, the introduction of a five-day working week in 1967 and easier travel within the Eastern Bloc led to a boom in tourism and camping, creating new leisure-based status symbols.

- The early 1970s saw a growing critique of consumer society by figures like Pasolini and Baudrillard, who argued it led to conformity and hollowness.

- In Japan (1970s), there was a rise in active outdoor leisure activities (asobi) and leisure parks combining education and entertainment.

- The 1973 oil crisis prompted temporary changes, such as the appearance of car-free Sundays.

- Despite a subjective feeling of being overworked, time-use diaries in the US showed that Americans actually worked less from the 1970s onwards, though middle-aged groups lost leisure time after 1980.

- 1980s – Present Day:

- By the late 20th century, the democratization of credit pushed traditional pawnbrokers and payday lenders to the societal margins.

- Anxieties about a “time famine” grew despite the proliferation of time-saving devices.

- The Slow Food movement was founded in 1989 in Italy, reacting against fast-food culture and evolving into a broader “eco-gastronomic” politics of sustainability and responsible consumption. This was followed by the Cittaslow (slow city) movement in 1999.

- The late 20th and early 21st centuries saw a significant increase in personal debt, particularly credit card debt in Anglo-American countries.

- In the 1990s, in Adelaide, Australia, the energy used to operate homes and transport was three to four times higher than the energy embodied in the products and infrastructure themselves.

- In 2000, France introduced a 35-hour work week, which increased weekend breaks.

- Modern digital communication tools like mobile phones and email provide users with greater flexibility to coordinate schedules and utilize “downtime,” potentially easing time pressure for individuals, despite common perceptions of increased busyness.

- Currently, economies are driven by spending, and even public services are often presented to citizens as products.

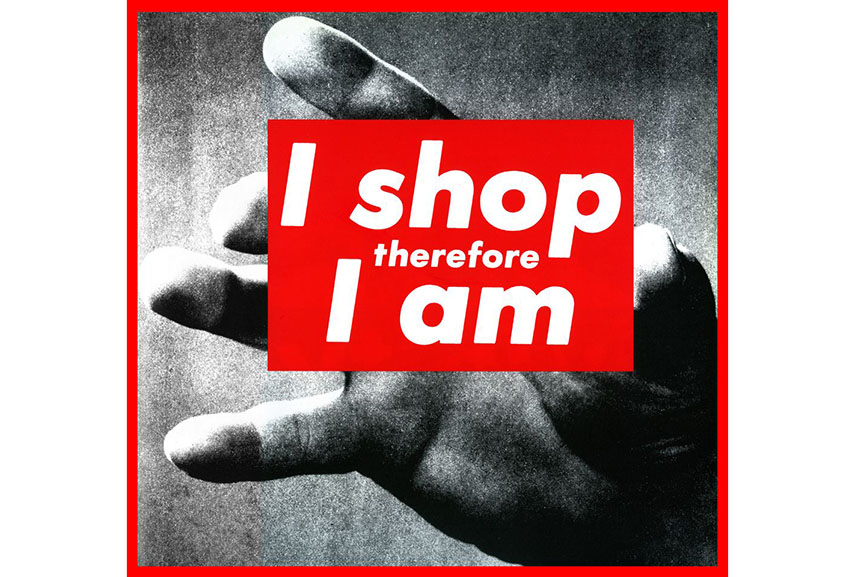

- Consumption continues to be a primary way individuals define their identities through taste, appearance, and lifestyle.

- The materially intensive lifestyle contributes significantly to environmental impact, with transport and larger, appliance-filled homes accounting for nearly half of global CO2 emissions.

- Movements for ethical consumption, such as fair trade and local food initiatives, persist, though their impact varies based on ingrained habits.

- New models like Repair Cafes and collaborative consumption are emerging, focusing on extending product lifespans and sharing.

- While Japan still has a long-hours work culture, its citizens report feeling less rushed than Americans, partly due to their ability to demarcate time for leisure.

- Food cultures have diversified; while “national cuisines” were a mid-20th-century invention, ethnic foodways adapt and persist through selective choices (e.g., Bengali-American families integrating American and traditional meals).

- The concept of a “throwaway society” has been debated, but modern societies have seen a shift from traditional reuse to disposability. However, there are growing efforts towards resource recovery and recycling. For example, US municipal solid waste increased significantly in total volume from 88 million tons in 1960 to 250 million tons in 2010.

- Asian societies have experienced centuries of Western consumer development (e.g., rise of middle class, domestic comfort, urbanization, home ownership) compressed into a much shorter timeframe.

- China (1949-1979) saw a reversal of commercial development under Maoism, with a drastic reduction in shops and services. Since liberalization, it has returned to an older commercial trajectory, becoming second only to the US in spending power (PPP) by 2009.

- India (1947-1990) prioritized self-sufficiency under Nehru, with consumption seen negatively, and its share of world trade fell significantly. In the 1960s and 70s, the Family Planning Programme used consumer goods like wristwatches and radios as incentives for smaller families in rural areas. Liberalization since is seen as a return to an older commercial path.

- Japan (1950s-1980s) experienced phenomenal GDP growth leading to mass purchases of TVs, cars, and AC units. Japanese companies actively marketed appliances as a fusion of tradition and modernity, creating a unique consumer experience (e.g., “Japanese colour” TVs).

- Overall, consumption has proven remarkably adaptable and is deeply embedded in political and social life, even being embraced by socialist and fascist societies as an ideal for “the good life”.